Is 'terminal anorexia' a thing?

It's a 'dangerous' and 'disturbing' term pushed by some US doctors...but is it as awful as it sounds?

I’d like to introduce you to my friend Dee. We met in hospital seven years a go, while we were both receiving treatment for anorexia. Somewhere between 64 and 67, Dee was like a cross between the woman manning the bumper cars at your local fun fair, and Barbara Windsor. Her cackle was omnipresent, rippling through the corridor and darting into the depressing group therapy room. She’d flick through The Sun newspaper every morning, with a fair amount of ‘CORR BLIMEY’ at whichever underwear-clad model made her mourn the ‘hips and stuff’ she insisted she once had. Every Thursday evening at 7.55pm, she’d shuffle down the corridor to the communal television room, demand silence, and switch on Doc Martin.

She demanded twice-daily trips outside for a fag, despite her thunderous cough. One morning, Dee shuffled past my room and saw me crying. I’d listened to the playlist my boyfriend made me. I missed him.

‘DARLING!’ She burst in. ‘It’s shit in here. They’re all bastards (gesturing to the nurse’s office behind her). But I’ll be your mum in here. I’ll look after you.’

And she really did. She’d remind me to put a coat on when we went on our daily outing to a rotten, old bench in the hospital garden. She’d offer to put washing on for me and occasionally do my ironing. We’d have boring chats about the cheap knitwear we’d found at various charity shops. The day before I left the ward, I told her she could keep one particular mothballed cardigan she’d admired. She wore it the next day and, according to some of the girls I briefly kept in touch with, most days for a couple of weeks. One time, the ward manager threatened to stop my brother visiting because I’d apparently had my quota of 15 minute hellos and goodbyes from non-mentally ill people that week. Dee hobbled up to the lead nurse, shook her walking stick in his face and shouted: ‘You’re fucking petty, you are.’

Dee had lived with anorexia since the age of 13. The illness had crumbled her bones; she could just about manage the corridor, but fag breaks required a wheelchair. Her skin was yellowed and baggy, and she could do with a trip to the hygienist or two. She was utterly devoted to her daughter and grandson, who lived in her hometown of Harlow – about a 45 drive from the hospital. Dee’s illness had strained their relationship. On several occasions, I heard her uncontrollably wailing while on the phone to her daughter.

Dee loved Mince Pies and Bakewell Tarts. But she’d only ever eat half of one, once a day. And she wouldn’t eat much else. While the rest of us were pretty much forced to choose either gloop-covered chicken or sweet potato with any form of protein on it, Dee got away with a few salad leaves, a couple of mushrooms and, I think, a slice or two of toast. Sometimes she’d finish dinner with a Fortisip – a high calorie supplement drink usually given to elderly people who can no longer chew food. It didn’t appear as though she was subjected to the same rules as the rest of us when it came to group therapy. While we sat in a circle talking about running away from barbecues, Dee sat happily in the TV room, laughing her head off at Bargain Hunt (I never understood what was funny).

I thought of Dee earlier this week when I read about Terminal Anorexia. It is a new, rather disturbing term, coined last year by psychiatrists based in US, which essentially allows patients to withdraw consent to all treatment. One clinician, Jennifer Gaudiani, based at the self-named Guadiani clinic in Denver, argued the case in a paper published in the Journal of Eating Disorders last February, which told of three patients with so-called severe and enduring anorexia (when treatments don’t work), who would, it’s implied, make good candidates for a diagnosis of terminal disease.

According to Gaudiani and colleagues: ‘Individuals should not be obliged to demonstrate extreme medical instability before having the right to choose to stop fighting.’ They also encourage healthcare professionals to consider the role of palliative care and hospices for some anorexia patients. She offers a criteria, to ensure no patient is ‘given up on’. They must, for instance, have had access to high-quality care in the past, be aged over 30 and have the mental capacity to consent to withdrawing treatment.

Predictably, there’s been a backlash. Several medical articles followed Gaudiani’s, suggesting that the concept would lead to ‘unjustified deaths’. The main opposing argument appears to be that the very nature of anorexia impairs a patient’s ability to make sound decisions about anything – not least whether they want to continue living. My instant reaction was passionate support.

But then I thought of Dee. Most of her fifth and sixth decades had been spent in NHS eating disorder units, living beside troubled teenagers who are terrified of life. When I met her, she’d occupied the same space in that particular NHS ward, on and off, for two and a half years. Most weeks she’d fail to gain enough weight to qualify for a trip home to her daughter. She’d pound the corridors for hours on end, screaming, sobbing. On one of her particularly sombre mornings, I’d tagged along for her fag break. I blabbered some crap to fill space: how group therapy was obviously centred on CBT, which famously doesn’t work for everyone. She looked at me with cold eyes and said: ‘I’ve had this for nearly 50 years. Nothing they do will make me better, sweetheart.’ I remember feeling furious at the system’s failure to save someone a magical as Dee. She’d been let down, over and over, by the state’s method of care. Dee wasn’t too ill to come back from the brink – the medical team must try harder.

In hindsight, I know it’s not always that simple. Studies show that without treatment in the first three years of illness, only a third recover. I had the best chances: no long history of eating problems, treatment within a year, a village of supportive overeaters, shiny prospects to recover to. And yet, it took me five years to really and truly get there. Maybe blind faith in recovery for all doesn’t give the wretched destruction of this illness enough credit. Does it pander to the idea that eating disorders are somehow in the control of the sufferer and ultimately fixable, if you want it bad enough?

Anyone who has been through a potentially fatal eating disorder will remember a time when they thought: ‘This may well be the end of me’. Mine came at an odd point in time - nine months after I was discharged from hospital treatment. My weight was stable and healthyish: healthier than most models on runways at London Fashion Week but not as healthy as when I’d left hospital. I was desperate to have a period again (when your weight drops below a certain point the body ain’t for baby-making) and was seeing a private dietician to help me put on a stone. My relationship with food, I thought, was mostly fine, and I was eating plenty – so why was I still shopping for kids’ clothes? At least three times a week I’d wake up sweating, trembling with fear about my self-inflicted broken reproductive system, telling myself; ok, tomorrow, we fix this.

An easy win, the dietician told me, was swapping my usual nothing-but-vegetables salad at lunch, for a small pot of pasta. Preferably one with creamy stuff on it. Sure, I thought, that’s easy enough. Fast forward 20 hours and there I am in M&S, staring at Food To Go like it was a cryptic crossword. I picked up a creamy tomato pasta salad – then put it back. Picked it up again, eyed up the 290 calorie broccoli and peas with mint dressing, remembered how safe it felt to eat, and put the pasta back. And so, for about a year or so, I continued to lose weight. Only one or two pounds – but every little helped. By that point, I’d had somewhere in the region of 100 therapy sessions – with two different therapists – six weeks of intense hospital treatment, around 40 dietician appointments (private and NHS) as well as an ocean of support from the people who love me. And still, I’d stand in the queue for the checkout clutching my plastic tub of green, thinking: ‘I don’t see how this gets better.’

Of course five years later, it has. Last night I ate so much Turkish food I couldn’t breathe and then went to the shop and bought a Flake for pudding. I’m not truly happy if I don’t have an emergency tub of Ben and Jerry’s in the freezer, and I’m currently looking at five Quality Street wrappers scattered across my bedside table. I eat pasta A LOT.

Is a similar metamorphosis possible for someone like Dee? After 40 years of illness, I’m not so sure. Should we allow her to deny herself the chance – even if it’s minimal? I’m not so sure either. Basically, I haven’t decided what I think about this yet. But I do know that living with anorexia is unwavering torture.

And after nearly 50 years of it, I wouldn’t blame anyone for wanting out.

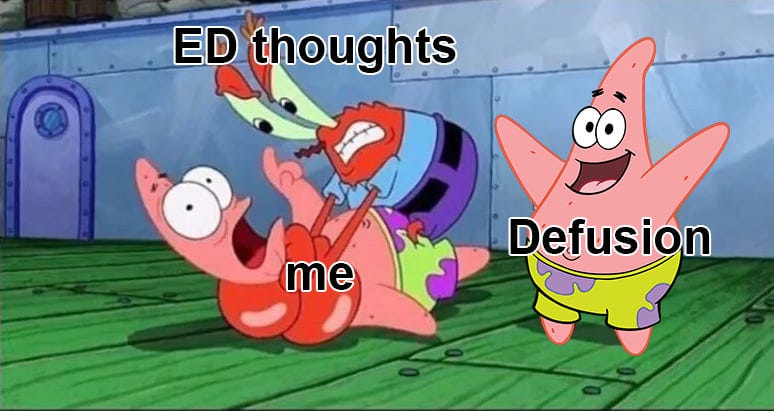

Image courtesy of facebook.com/EDrecoverymemes

I appreciate your perspective on this and thank you for sharing the story of lovely Dee. I think the problem with Gaudiani’s article is the emphasis she placed on medical assistance in dying (MAID). She acknowledged that for some people with extremely severe, long-term and seemingly treatment-resistant anorexia, there are cases where a palliative approach, focussing on harm reduction and comfort, rather than a recovery-focussed approach, would be more appropriate. Like in end of life hospice care, in the very severe stages of this the focus would be on spending time with family and reducing pain. In this approach the more peaceful time and focus on keeping existing relationships might be comfort before death and in some cases can foster some hope for recovery. But I think the idea of ‘terminal anorexia’ requiring MAID is so dangerous - I imagine it is almost ubiquitous that at some point in an ED you believe that you will never recover and would be better off dead. Gaudiani endorsing the idea that there are some people who can never get better - in some equivalence to those with something like an incurable cancer - is a really dangerous idea to put out onto the internet for vulnerable people who are at this very lowest stage might find. I have certainly been at this point and having persistent reminders that even though it is extremely difficult, I could (and did!) recover was so valuable. It seems that in the NHS, there is not a provision for palliative care for these severe cases. But a gentle end of life (assisted by pain relief as in other hospice care) could have been an option for the patients described in the original article, which is very different from administering MAID when death would have been far off for them. Sadly I think Gaudiani’s article will already have done some damage by making people who would go on to recover believe that there is no hope for them. I really recommend Mack & Stanton’s response (Responding to “Terminal anorexia nervosa: three cases and proposed clinical characteristics”) in Journal of Eating Disorders which I think provides an empathetic and reasoned argument against Gaudiani here.