As far as I knew, Elon Musk’s expertise extends to tech firms, huge tax bills and designing ginormous, heinous trucks that look like the backend of my dad’s first ever PC.

But apparently, he is also an expert in women’s health - according to one of his tweets (X’s…?) posted last week.

‘Hormonal birth control makes you fat, doubles risk of depression & triples risk of suicide. This is the clear scientific consensus but very few people seem to know it.’

Many readers may, to their horror, find themselves nodding in agreement with Mr Musks’ statement.

Women in my life have aired grievances with the contraceptive pill for as long as I can remember. It made them gain weight they couldn’t shift, it gave them spots, it made them feel exhausted, hangry, just not quite themselves.

I’ve long been endlessly fascinated by these claims, not only because of the frequency I hear them, but because my personal experience has been the total opposite.

I took microgynon (the boring, generic one that comes in white packet with green writing) between the ages of 18 and 28, albeit with a few brief breaks. I never suffered a single side effect until aged 31 when I went back on the same pill and had a few incidences of irregular bleeding. I considered myself extraordinarily lucky to be of this disposition, or maybe I was too distracted by the rampant eating disorder than punctuated my 20s to notice.

Working as a health journalist only added to my confusion. Gynaecologists and women’s health experts I encountered went to great lengths to argue that the risks of The Pill had been ‘overstated’. One senior doctor I spoke with went as far as to say the drug is perhaps one of the 21 century’s most studied medicines, making it exceptionally safe. This is at odds with passages in several recently-published non-fiction books, which highlights the ‘lack of long-term safety data’ regarding The Pill, given that we only have 60 years of research to draw on.

So what’s the truth?

It is true that, just by nature of its relative infancy, information about the long term effects of The Pill is limited. But this is not a reason to discount a drug, or assume it is unsafe.

Vaccines, for instance, which have been proven safe (despite what some corners of the internet think) time and time again since their introduction in the 1700s, were rolled out in the absence of long-term studies. But the smallpox vaccine alone is estimated to have saved 300 to 500 million people over the last 100 years. The Covid-19 jab is another famous example of speedy access - and high-quality studies continue to prove that the benefits far outweigh the risks for all groups, including pregnant women.

According to Dr Anita Mitra, gynaecology researcher and NHS hospital doctor, The Pill has been ‘unfairly critisized’, and there’s little evidence to suggest weight gain and skin problems are a significant risk.

The data on the combined pill (progesterone and estrogen) overwhelmingly supports this.

On acne: a 2012 review of 31 trials, including high-quality placebo controlled studies, involving more than 12,000 women, found no worsening of skin problems.

In fact: ‘The six pills studied in trials with placebos worked well to reduce facial acne.’

As for weight gain - ‘Most comparisons of different combination contraceptives showed no substantial difference in weight…no large effect was evidence,’ according to a 2014 Cochrane review of 49 medical trials.

What about mental health? In 2016, a study of a million Danish women found that those taking the oral contraceptive pill (both combined and progesterone only) were significantly more likely to suffer depression than those who didn’t.

However commenting on the findings, several of the UK’s top women’s health experts noted that this does not mean The Pill causes depression, as the researchers only looked at links between the two. It might very well be the case that women with a vulnerability to mental health problems are, for whatever reason, more likely to take hormonal contraceptives.

But Dr Channa Jayasena, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Reproductive Endocrinology, Imperial College London, said that the link was certainly possible, given what we know about hormones and their profound impact on mental health.

Although, in 2021, scientists from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands attempted to establish this causal effect, analyzing results from 12 trials involving more than 5,000 women. They concluded: ‘compared with placebo, hormonal contraceptive use did not cause worsening of depressive symptoms.’

Another study of 6,000 women from last year actually found that women who take The Pill are less likely to suffer depressive symptoms.

Some researchers have identified that a well-known medical phenomenon called the ‘nocebo effect’ applies to the contraceptive pill. This describes the well-evidenced impact of negative ‘noise’ about a specific treatment. In other words, if you believe a medicine will cause certain symptoms, it probably will.

It goes without saying that everyone is different - and I am not, by any means, looking to diminish any woman’s experience of a medication. There may well be mood problems caused by The Pill. But the fact is that, so far, when scientists have tried to find said psychiatric symptoms, they simply aren’t there.

There is one well-proven side effect we should all take seriously. Estrogen-containing contraceptives increase the risk of a potentially life-threatening blood clot two to six-fold, according to studies. However, even with this risk, the chances of it happening are extremely low.

Around one in 3,000 women who take The Pill will experience a blood clot every year, according to The National Blood Clot Alliance in the US. In comparison, some two in every 1,000 pregnant women will suffer one.

It’s also worth mentioning that the risk of blood clots with the progesterone-only pill is not raised at all, nor is it with hormonal and non-hormonal IUDs.

If I’m honest, I find the discourse around The Pill a bit depressing. It is perhaps the single most revolutionary medicine of the last 100 years - for both medical and societal reasons - expanding opportunities and horizons for every woman on the planet, and yet all we seem to talk about is its (relatively minor) flaws.

The Pill was approved as an oral contraceptive in 1960 in the USA, and 1961 in Britain. In 1976, 73 percent of all single women between 18 and 19 years old in the USA had used the drug.

(FYI the IUD wasn’t available in the UK and US until the late 90s/early 2000s).

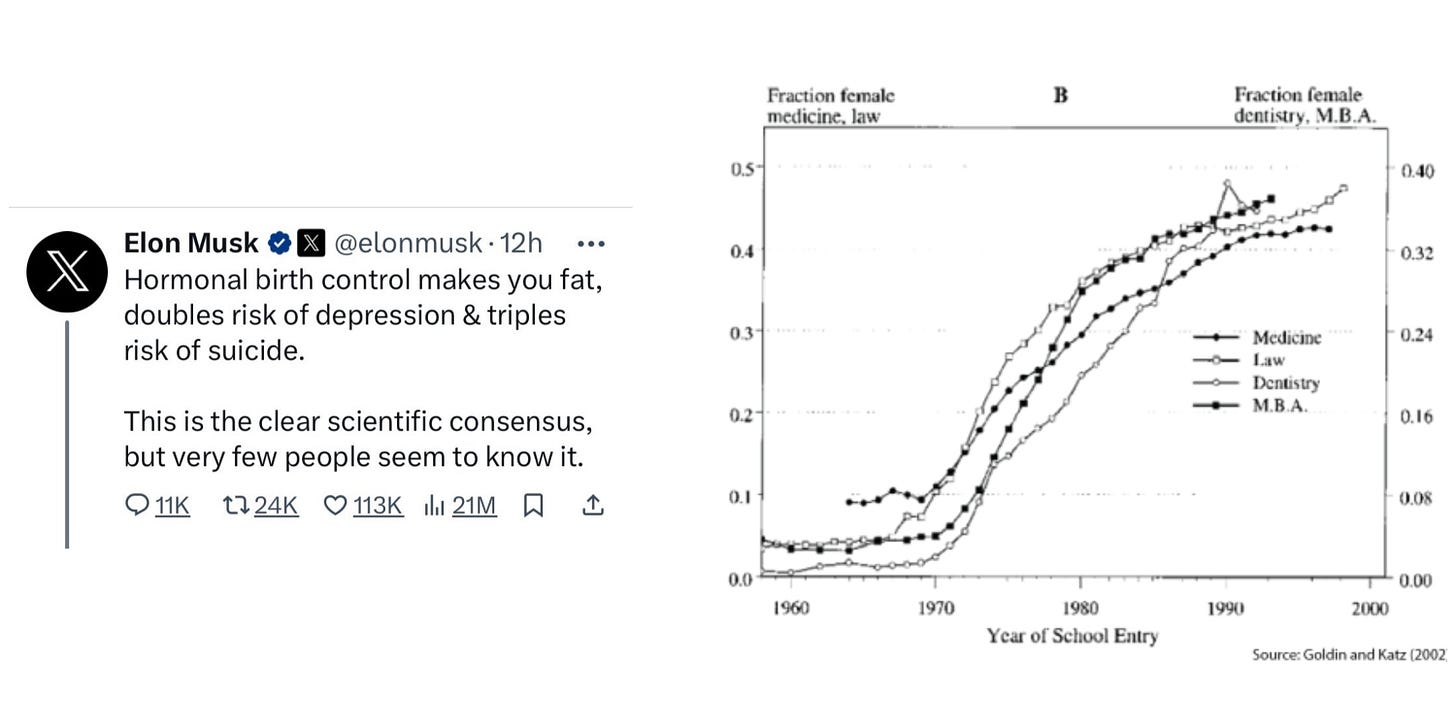

In 1970, medical, law and business degrees in the US were over 90 percent male. By 1980, a decade after access to The Pill was available in most states, they made up roughly a third of students.

The medicine, taken by 150 million women worldwide, has gifted us bodily autonomy, the freedom to govern our own destiny, the ability to marry for love not convinience, not to mention surplus income.

According to the Joint Economic Committee Democrats, women with access to contraception in their early 20s earn around $2000 more per year, compared to those who don’t.

The risks of unwanted pregnancies are, in my opinion, not given enough attention. Studies show women who have babies they don’t want are significantly more likely to, well, have a shit life. They have higher chances of: ending up in violent relationships, suffering mental health problems, financial problems and becoming homeless, compared to those who don’t. There’s risks for the children too; namely behavioural and mood disorders.

Like any drug treatment, The Pill is not perfect. By their very nature, all pharmacological interventions have side effects. But maybe, sometimes, it’s okay to focus on the vast array of positives a drug has brought for us, rather than picking at its potential negatives. Especially when said drug has literally transformed life for, oh I don’t know, half the human population.

So, yeah, thanks Elon for your input but probably best you stick to making big, ugly cars.